Eco-death by degrees

Eco-death by degrees

Q: Q uestion for biology professor Ray Heithaus '68: We read and hear conflicting views about global warming, ranging from denial of the phenomenon to dire predictions of world destruction. How worried should we really be? Is there anything we as individuals can do?

A: Global warming is like a weather forecast: there is a range of possibilities. If we get the worst end of the range, we should be pretty darned concerned. Over a time scale of the next decade, the concerns would be not too high. But over fifty years or longer, they start to

get serious.

Science is pretty clear about changes observable in the atmosphere now, but we don't know a lot about how disruptive the changes are going to be. The change almost certainly will be more subtle to start with than the flooding and disasters you see in the movies. The rise in sea level will happen down the road, but recent studies indicate the time scale is fifty to one hundred years. I'm not going to be alive when that happens, so I'm concerned for my grandchildren but not for me.

We're already seeing changes in the distribution of plants and animals around the world. They're shifting away from the equator toward the northern and southern latitudes into regions where they previously weren't very common. Also, the surface of the oceans is warming now, and this contributes to a higher intensity of hurricanes.

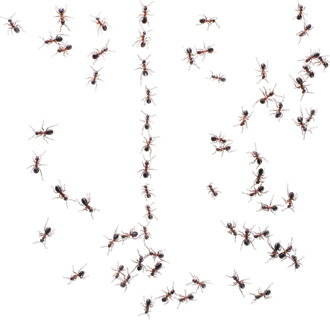

I have altered some of the questions I'd like to examine in my own research, which focuses on dispersal of seeds by ants. The timing of seed production for the plants is dictated by one set of cues in the environment, but the timing of colony growth for the ants is responsive to a different set of cues. If those processes get displaced by too many changes in different directions, the food that the ants need in order to succeed will not be available.

A root issue for environmental concerns is that each of us individually has a very hard time seeing how our personal behavior impacts anything on a scale that matters. Here's just one example taken from U.S. census data. From 2004 to 2005, the average size of houses increased by 63 square feet. This is about the size of a closet, so one might ask whether we should care. Multiply this by the 2,064,700 new houses in the U.S., and we see that even though family size has decreased, we are allocating about 28,905 football fields--not counting end zones--per year to living space that could otherwise have stayed in forest, farmland, or pasture. Lot size also increased by an area about 90 feet by 50 feet. Again, not so much on an individual scale, but it adds up to about 217,000 acres per year. And that's just the increase from the 2004 housing base. Overall, we are adding 770,000 acres of new housing per year.

It's a multiplication of all of our tiny little contributions over a huge number of people that causes problems. And you can't really expect individuals to see that and respond to it. It's not part of our daily experience. But we have to try to adjust our behavior so our children and grandchildren don't have to pay the price.

Ray Heithaus '68 is the Jordan Professor of Environmental Science and Biology. A driving force behind Kenyon's Brown Family Environmental Center, Heithaus was a founder of the College's environmental studies concentration.

Do you have feedback on this page?