Dance Weekends were a time for dressing up, and occasionally dressing silly. Front-page stories in the Collegian would hype the event, sometimes playfully. A May 1954 story proclaimed Gambier “the center of the universe,” playing host to “beautiful girls from all over these United States.”

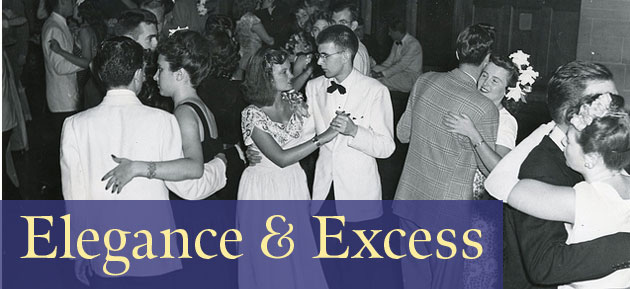

The gowns swirled and the faces glowed. The music swelled; the drinks flowed. Steeped in cigarette smoke and body heat, the parties spun toward dawn. Sweetheart or blind date, it didn't matter: the opposite sex was on the scene. The boy-island with its all-boy routines had dissolved. In its place, a short-lived—intensely lived—eternity.

Dance Weekend endures, in memory and in Kenyon legend. For student generations from the 1940s into the 1960s, the very phrase “Dance Weekend” evokes visceral echoes of the social year cresting in two eagerly anticipated splurges, one in November, one in May. Dance Weekend was a festival of elegance and excess, a release, a holiday from the hilltop humdrum, when the usual rigors of work and play yielded to a two-day, all-play world with its own set of rituals: the arrival of the buses filled with girls, the cocktail parties, the big-name bands, the dancing, the romancing, the pranks and stumbles, the couples' quest for a private spot, the bleary Sunday mornings at the football field with a tub of “milk punch.”

Coeducation and changing social habits brought an end to the era of Dance Weekends. The music that came to campus changed, too—Count Basie gave way to Blood, Sweat & Tears. The rules, in everything from dancing to wooing, blurred or vanished, for better or worse. But, lest the last lights go out without another song, the Bulletin editors dipped into the archives, and into some alumni memories.

The story's a simple one. Dance Weekend opened her arms, and Kenyon surrendered. Here's a taste of what it was like.

Quick! Hide My Date!

Quick! Hide My Date!

Richard Kochmann '66 frowned on Dance Weekend carousing, but he was willing to help a friend “who didn't want to get caught at two in the morning, when campus security was scouring [Old Kenyon] for any female companions that may have chosen a ‘sleep-over.'” Kochmann's sterling reputation made it less likely that his room would be searched, so the friend asked him to hide his date. “In those days, the closets of Old Kenyon had raised fake wooden floors, like a trap door for a secret compartment below. His petite and lovely date fit nicely into this section. After sufficient time had passed, the couple reconnected and were together for the rest of the night without disturbance or any consequences.”

“Cattle Cars” and Blind Dates

While Kenyon had “hops” and “promenades” in earlier years, the classic Dance Weekend era began in 1938, when President Gordon Chalmers decided to ease the campus's social isolation by recruiting a busload of women from his former school, Rockford College in Illinois. After a four-hundred-mile, thirteen-hour drive, the forty women (accompanied by a Rockford dean) alit in Gambier—and were promptly matched with Kenyon men by economics professor Paul Titus, who purportedly based his pairings on age, height, and weight.

Thus began the tradition of “cattle cars” arriving from women's schools in a kind of mass blind date. (Later, the practice was to have the men line up when the bus arrived; each woman, as she stepped down, was paired with whoever was next in line.) Many Kenyon men arranged their own dates with women from Denison, Ohio Wesleyan, and Ohio State. But the buses kept coming; one popular source of weekend dance partners was Lake Erie College for Women in Painesville, Ohio. The women were housed in freshman quarters (the freshmen had to double up in other dorm rooms for the weekend) or were invited to stay in the homes of faculty members or townspeople.

“April in Paris,” in Gambier

Top names in music played Dance Weekend. During the 1950s, “The Singin' Rage” Miss Patti Page headlined at Kenyon. Jazz great Maynard Ferguson, trumpeter Ray Anthony, and Ralph Flanagan with his Glen Miller sound all brought their bands to campus. Kurt Riessler '57 remembered saxophonist Rusty Bryant playing hits like “Night Train” and “All Night Long” in one of the fraternity lounges on a Saturday afternoon before the big dance.

And then there was the legendary Count Basie, who played with his orchestra at the spring Dance Weekend in 1955. “Basie's famous version of ‘April in Paris' was on the Top 40 list of popular songs and on the Top 10 list of R&B music,” wrote Phil Levering '60. “I remember standing next to the piano, without moving more than a few feet from the Count himself, for several hours.” Bruce Olmstead '57 recalled that Basie and guitarist Freddie Green “went down to one of the frat lounges afterward and jammed all night. Freddie Green just sat there and smiled and strummed his guitar. It was lovely.”

As the sixties rolled on, the music edged from dance performance into concert, as Kenyon signed leading figures in rock and roll, rhythm and blues, folk, and soul. The entertainers included: Bo Diddley, the Smothers Brothers, Little Richard, Nina Simone, Odetta, and Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. Later, there were the Youngbloods, the Gary Burton Quartet, the Incredible String Band, the James Cotton Blues Band, Maria Muldaur, Sam and Dave, Poco, and Blood, Sweat & Tears.

It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time

It Seemed Like a Good Idea at the Time

High spirits enhanced by alcohol produced a certain anarchy during Dance Weekends. Pranks and general silliness abounded. John Perry '49 remembered how his brother Stewart '48, inspired by Mark Twain's Pudd'nhead Wilson, once stole a chicken from a local coop. Lacking a pot of boiling water, the brothers plucked the feathers under a hot shower and tried to barbecue the bird in a North Leonard fireplace, using a curtain rod as a spit. They never managed to get it fully cooked but ate what they could anyway. “It was a terrible fiasco,” said John. “But we were hungry.”

Milk Punch: The Secret Ingredient

“Almost all the guys had a bottle of some kind of liquor for the weekend,” recalled Bruce Olmstead '57, describing the Sunday-morning milk-punch parties, when the early risers (or up-all-nighters) gathered around a metal laundry tub at the football field. “Anybody that had anything left in their bottles would pour it in.” The women took off their shoes, getting grass all over their feet, and stepped into the tub to stir. “Then you and your date walked around drinking milk punch out of your bottle.” Olmstead's verdict on Dance Weekends: “a very happy and civilized sort of mayhem.”

Happily Ever After

Perry Lentz came to have mixed feelings about Dance Weekends, which were draining marathons—in the sense of both physical exertion and the consumption of alcohol. “There was a lot of drinking on regular weekends,” he wrote in a recollection of those years. “But people budgeted financially and personally for these huge weekends and anticipated drinking a great deal.”

Lentz went on, “My memories of accompanying a date into the Great Hall for the Saturday night climactic ‘Dance' are all occluded by the recollection of being completely exhausted by that hour: head already hurting, feet already hurting, and with the prospect of hours yet to go.”

Lentz '64 P'88 H'09 would eventually return to spend a forty-year career as a Kenyon English professor, earning distinction as a superb teacher with exacting standards and a formal bent that might seem at odds with the antic spirit of Dance Weekend. But one of those weekends changed his life. It was at a Dance Weekend that he met his wife Jane, a student at Lake Erie College for Women. A blind date had been arranged by friends. The marriage is into its forty-eighth year.

Delicious

Delicious Facebook

Facebook StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Digg

Digg reddit

reddit