Teaching Terrorism

Teaching Terrorism

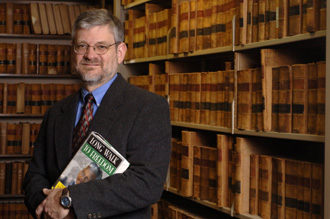

Associate Professor of Political Science David M. Rowe pushes his students to recognize the disturbing "moral logic" of terrorism

Terrorism is the most challenging subject that I teach. One must navigate many treacherous shoals, ranging from simply condemning terrorists as evil--a morally gratifying position that nonetheless obscures the motives, reasons, and purposes behind terrorist violence--to the oft-repeated cliche that "one man's terrorist is another man's freedom fighter," a rhetorical device most often intended to shut down inquiry. My objective is to get students to see the world through terrorists' eyes, to comprehend their moral universe, and to understand how and why terrorists use violence as a political instrument.

Simply defined, terrorists are nonstate actors who use violence to challenge the established political order. Terrorists can range from black militants seeking majority rule in apartheid South Africa, to white supremacists seeking a racially pure America, to Islamist fundamentalists seeking a new caliphate in the Middle East. What these groups share is that they all see a world dominated by an oppressive and unjust state that uses its overwhelming capacity for violence--the military, the police, and the courts--to impose and protect an order that is deeply flawed and morally corrupt. Terrorists turn to covert and surreptitious violence because they see it as the only effective instrument by which to achieve their vision of the just society in the face of a vastly more powerful opponent.

One of the key texts in my terrorism seminar is Nelson Mandela's autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom. This may seem a surprising choice; many admire Mandela as a hero, who won the Nobel Peace Prize for helping to bring about an ultimately peaceful transformation in South African society. But Mandela's book offers insight into terrorism by explaining how the apartheid regime confronted blacks with a stark moral choice. Because the regime ruthlessly used its police and security forces to suppress any black demand for political equality, change within the normal channels of politics was impossible. Either South Africa's blacks could acquiesce to the moral degradation of apartheid, or fight the regime on its own terms--with violence.

For the terrorist, the violent act is not an expression of frustration, hopelessness, or despair, but a political instrument to weaken a corrupt and oppressive regime, defend those who suffer from its excesses, and ultimately realize a vision of the just society. It is a moral claim submitted by the terrorist on behalf of the unjustly oppressed and an affirmation of their human dignity. Menachem Begin of Israel, also a Nobel Peace Prize winner and a heroic figure for many, suggested the defining role of violence when he wrote about the Irgun's struggle against the British occupation: "We fight, therefore we are."

The idea that there is a moral logic to terrorism--and that even leaders like Mandela and Begin articulated this--is deeply unsettling to students. Some feel that to acknowledge this moral logic is to accept the validity of the terrorists' claims and justify their actions. More than once, I have been accused of justifying terrorism. But explaining the moral logic of terrorism does not imply that any terrorist's moral claims are valid. It does, however, provide insight into why terrorists can commit atrocities, maintain that these acts have moral purpose, and generate and sustain--through violence--support for their political agendas.

Other students argue strenuously for the moral superiority of non-violent political action. But this provides little insight into the terrorist mind. For the terrorist, the belief in nonviolence as a fundamental principle is naive. Not only does it conveniently ignore that the state routinely uses violence to enforce its laws and impose an unjust order, but an attachment to nonviolence also means that one's ability to fight injustice becomes limited by the brutality of the other side, for the more brutal they become, the less scope for action you possess. "There is no moral goodness," writes Nelson Mandela in criticizing the principle of nonviolence, "in using an ineffective weapon."

Over time, my students come to see that terrorism emerges from a struggle about how to structure the just society, and that it is the moral logic of terrorism that makes it so dangerous. Just as the state uses its instruments of violence to establish and maintain a certain political order, terrorists use violence to challenge and de-legitimate that order. But whereas the state's use of violence is constrained within the rule of law and its responsibility for maintaining public order, terrorist violence not only occurs outside these rules and obligations, it is a fundamental rejection of them. This leads to the most unsettling insight of all, for it implies that terrorism is nothing less than the unconstrained use of violence infused with a sense of high moral purpose. A more deadly combination is scarcely imaginable.

--David Rowe began teaching a terrorism course at Kenyon shortly after the September 11 terrorist attacks. His courses fill up quickly each semester.

Do you have feedback on this page?