Touching the Page, Finding the Past

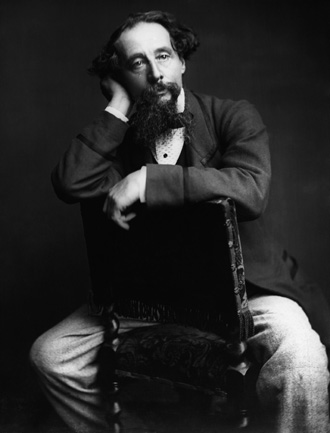

I don't remember how I fell in love with archival work, but I think it had something to do with Charles Dickens's hair.

I don't remember how I fell in love with archival work, but I think it had something to do with Charles Dickens's hair.

Four months after I graduated from Kenyon, the rare books curator at Cornell University, where I'd just started my doctoral program, presented to my Victorian fiction seminar what looked like a leather-bound book. Its spine read Charles Dickens: Lock of His Hair. Inside this book-shaped box, one perfect piece of brown hair curled under glass, paired with a certificate of authenticity signed by Dickens's sister-in-law. This relic, she claimed, had come from as near as one could get to the great author's brain.

In the ten years since that lock of hair sent a shiver down my spine, I've spent many enthralled weeks in archives and manuscript collections, in both the United States and the United Kingdom, touching the things that writers have left behind. Those things have not often been physical remains; instead, they've generally been manuscripts of the British Victorian autobiographies on which my scholarly work focuses. I return to archives again and again because of the breathtaking liveliness of the things I find in them. And I return because I love being the first to find those things.

I spent July 2001 doing dissertation research in the London Library, poring over the two enormous volumes of John Addington Symonds's Memoirs. Written between 1889 and 1891, the Memoirs detail Symonds's painstaking attempts to reconcile his same-sex desires with his respectable life as a well-known English historian and man of letters. Though parts of the manuscript were published in 1895 and others in 1984, much of it remains unknown to all but a very small number of people.

With each page I turned that summer, and with each excised passage I typed into my laptop, I felt a strengthening sense of myself as one of this work's knowers, one of its scholarly guardians. I was turning the pages Symonds himself had turned; I was handling the textual fragments--such as his wife's handwritten journals detailing their engagement and wedding--that Symonds himself had collected and pasted into his manuscript. And I was noting, in a way no one else had done, the marks earlier readers had left behind them.

At one moment late in the manuscript, Symonds's first editor penciled out two instances of the word "love" and, in the margin, tried to replace them with "lust" and "affection." Beneath this marginal note was a reply from Symonds's youngest daughter (who could only read her father's autobiographical manuscript in the library, with its permission, in the 1940s), imploring future readers and editors to "Let JAS words stand." Because I knew her handwriting and her initials, I made a connection that no one else had: I recognized a daughter's defense of her long-dead father.

That find exhilarated me. It also broke my heart. Since then, I've worked with other Victorians' remains: Thomas Carlyle's reminiscences of his wife, written partly in one of her journals; John Ruskin's autobiographical drafts, which also detail his dark depressions; Margaret Oliphant's notebooks, with their inky fingerprints and broken locks.

The materials that archivists and manuscript librarians unearth at my request travel to me from mysterious vaults. When I finish with those fragile volumes and repack them in their often ingenious wrappings and boxes, they go back to waiting for the next curious scholar. Sometimes, the process of summoning the pages in which my subjects penned their lives' stories--and of joining the ranks of readers who have studied them before me--feels uncannily like calling up the dead. Sometimes, especially after I've spent weeks with a manuscript and become fiercely attached to the man or woman who wrote it, sending it back to storage feels like commanding a reburial. Sometimes, as I carry new knowledge of these materials away with me, I wonder what traces of myself I leave behind with them.

Do you have feedback on this page?