Junk and Dreams

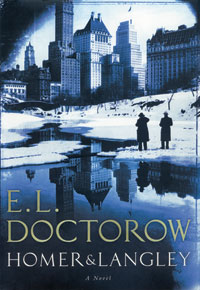

Published last fall, E.L. Doctorow's novel Homer & Langley (Random House) re-imagines the Collyer brothers, real-life eccentrics who compulsively filled their New York brownstone with junk before dying amid their clutter in 1947. Set inside the brownstone as the brothers bury themselves in the debris of civilization, while occasional visitors offer glimpses of how society outside is speeding through decades of change, the book unfolds in the engaging, old-fashioned voice of Homer, the blind brother—"a man with nothing to show for his life but an overworked consciousness of it."

Published last fall, E.L. Doctorow's novel Homer & Langley (Random House) re-imagines the Collyer brothers, real-life eccentrics who compulsively filled their New York brownstone with junk before dying amid their clutter in 1947. Set inside the brownstone as the brothers bury themselves in the debris of civilization, while occasional visitors offer glimpses of how society outside is speeding through decades of change, the book unfolds in the engaging, old-fashioned voice of Homer, the blind brother—"a man with nothing to show for his life but an overworked consciousness of it."

"It was as if the times blew through our house like a wind," says Homer. Indeed, the novel becomes an eloquent meditation on the immense shifts of twentieth-century American culture, and on time itself—on mortality—as well as on material life and the life of dreams, memories, and the mind.

If Homer is "defective," as he himself puts it, Langley is damaged as well, having been gassed in the First World War, an experience that drives him into unremitting cynicism, while leading him to forsake normal aspirations for ingeniously insane projects. He amasses newspapers, for example, with the aim of creating an "eternally dateless" paper that would "fix American life finally in one edition."

His derangement and paranoia are accompanied, however, by his devotion to Homer, by Homer's equanimity, and by a kind of sweetness that suffuses the household, an innocence rooted partly in isolation—the brothers have stranded themselves on an island moored to the past—and partly in a yearning for love. It's also an American innocence. For although Langley relentlessly rails at the foibles of his countrymen, his schemes reflect that distinctively American faith in redemption through persistent tinkering.

The reclusive brothers view the world from a distorted but provocative angle. The monumental filth of their home and the increasingly angry ravings of Langley may be appalling, but so is a world where bigots bomb children in a church, cult leaders convince their followers to drink poisoned Kool Aid, and death squads rape and murder nuns.

The world's debasement is reflected in its sensory stuff, teeming even as it goes to ruin. But Doctorow's richly textured prose suggests a love for the sensuous stuff of life as well. With Langley adding typewriters to the household collections, Homer (who has always played the piano) hears "a new music ... of key clacks and bell dings and slamming platens." One machine "felt to my touch like a metallic butterfly with its wiry wings in full flight." Elsewhere, Doctorow describes a black cornetist improvising on gospel hymns: "The music rose up through the walls and spread through the floors so that it seemed as if our house was the instrument."

The same might be said for this novel, which resonates with verbal music. "I am telling you what I know," a friend tells Homer—"words have music and if you are a musician you will write to hear them." Doctorow has composed a compelling symphony.

—Dan Laskin

Delicious

Delicious Facebook

Facebook StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Digg

Digg reddit

reddit