Volume 31 Number 3 Winter 2009

In this Issue

Features

- Kenyon's Own

- Out of the Ashes

- Peirce Hall Reborn

- Ancient Empathy for Warriors

The Editor's Page

- Restoration Drama

Along Middle Path

- Going Solo

- Seen and Herd

- Jersey Boys (and girls)

- Sound Bites

- Kenyon in the News

- The Hot Sheet

- Gambier is Talking About...

Sports

- Sports Round-Up

- Gaining Something In Translation

Books

- The Heart of the Matter

- Reviews

Office Hours

- Musings: Beginner's Mind Over Matter

- Not in my Job Description: Lyrical Baker

- Burning Question for Jennifer Delahunty, Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid

Alumni News

- PTSD Sleuth

- Driveway Moments

- Obituaries

- Alumni Digest

The Last Page

- Peircing Memories

By Dennis Fiely. Photography by Troy T. Heinzeroth, Howard Korn, and Davis Turner.

Related Stories

Charles Thompson

Captain Charles Thompson '02 was an army fire support officer in Afghanistan. Read Thompson's story.

Captain Charles Thompson '02 was an army fire support officer in Afghanistan. Read Thompson's story.Donald Cole

Donald Cole '01 was an army platoon leader in Iraq. Read Cole's story.

Donald Cole '01 was an army platoon leader in Iraq. Read Cole's story.Rick Horak II

Major Rick Horak II '90 was an Air Force Reserve flight surgeon in Iraq. Read Horak's story.

Major Rick Horak II '90 was an Air Force Reserve flight surgeon in Iraq. Read Horak's story.Bryan Doerries never served in the military, went to war, took or returned enemy fire. But that hasn't stopped him from fighting a home-front battle on behalf of American troops struggling to cope with combat experiences.

The former Kenyon classics major is founder and director of The Philoctetes Project, an unusual form of psychodrama intended to salve the wounded psyches of soldiers. Doerries formalized the venture earlier this year to stage his translations of ancient Greek plays for military audiences.

"Why am I inviting veterans and active-duty military to see 2,500-year-old dramas?" Doerries asked, repeating a common inquiry. The answer resides in works that deal with timeless themes related to combat stress. The New York City director believes that professionally acted readings of his translations can spark public discourse about and private examination of war's psychological consequences, often exacerbated by silence and repression.

Reaction to a September 16 presentation at the Juilliard School in Manhattan indicated that Doerries' initiative is having its desired effect. When, during a post-performance panel discussion, psychiatrist Jonathan Shay questioned the therapeutic value of "passive observation" of war-related scenes, U.S. Army Major Joseph Gerarci would hear none of it. "It helped today!" Gerarci interrupted from the second row.

Nobody dared question the officer's credentials as a critic: he wore them on his lapels. A native of Edgewood, Kentucky, Gerarci served two tours in Afghanistan, where his best friend was killed. His protest validated the virtue in Doerries' effort to help proud warriors overcome the crippling guilt and depression of combat-induced post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), expressed by flashbacks, insomnia, divorce, substance abuse, and suicide.

The Philoctetes Project tackles PTSD and the military's treatment of its disabled with scenes from two plays by Sophocles: Ajax tells the story of a war hero's suicidal descent into madness, while Philoctetes details the abandonment and isolation of a wounded hero two and one-half millennia before deplorable conditions at Walter Reed Army Medical Center emerged as a national scandal.

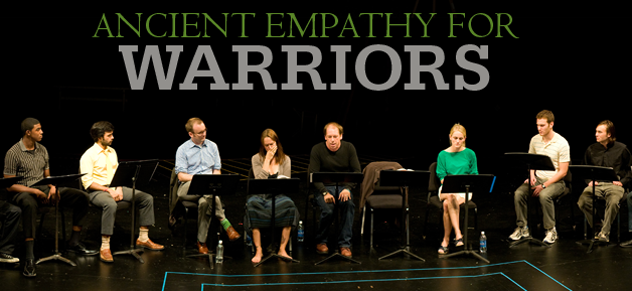

The minimalist interpretation at Juilliard revealed the power of unadorned words and emotions. There were no costumes, sets, or props. The director's company of accomplished New York City actors sat simply in a semi-circle on the barren stage, reading their lines from behind metal stands holding their scripts. Doerries joined them onstage. With his left arm draped over the back of his chair, he angled his body toward the cast, hanging on every syllable and beaming like a proud papa over the accomplishment of an offspring.

And why not? These are his words, funneling the stories and insights of Sophocles, the great Greek tragedian. Doerries tailored his translations for contemporary consumption with updated language ("shell shocked") and graphic images ("severed heads, snapped spines," "ripped-out tongues"), trying, he said, "to find the right words for this moment in time."

When the wife of Ajax described her husband's psychic paralysis as "the thousand-yard stare," U.S. Army Major Ray Kimball, an Iraq war veteran recovered from PTSD, nodded with recognition. Doerries expanded the literal translation—He lies (inside), disturbed by a tempestuous disease—into phrasing more specific and meaningful to the modern military—He sits shell shocked inside the tent, glazed over, gazing into oblivion. He has the thousand-yard stare.

"I'm astounded by how much these plays resonate with my experiences and those of my friends and colleagues," Kimball said. "The commonalities are stunning. I can say with complete certainty that every military man and woman in this theater has seen something of themselves in those characters onstage."

William McCulloh, Kenyon professor emeritus of classics, praised his former student's translations for striking a delicate balance between fidelity and relevance. "Translators have to adapt their work so their native languages can capture it," said McCulloh, who watched Doerries direct Kenyon drama students in a three-hour performance from The Philoctetes Project in Peirce Hall last spring. "There is no one formula for translations. Some are remarkably close to the original, while others are wild and woolly. Bryan falls squarely in the middle. He gives his translations an immediacy, without introducing his personal distortions."

Doerries seeks an immediacy that speaks to the 1.7 million troops who have served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Of those with combat exposure, up to twenty percent will suffer from PTSD symptoms, according to case reports by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Many cases are unreported, according to clinical psychologist Martha Schulman '74, who counsels PTSD patients at Hunter Holmes McGuire Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Richmond, Virginia. "The rate is steadily climbing and the amount of resources devoted to treatment is shameful," Schulman said.

She welcomed The Philoctetes Project, with a caveat. "Because these plays are so old, they may help normalize something that soldiers have felt for thousands of years," Schulman said. "But veterans don't respond to treatment in the same way. We have to be careful not to re-traumatize them."

Treatment encompasses traditional psychoanalysis and forms of cognitive behavioral therapy geared toward helping veterans identify and change distorted thoughts, Schulman said. In severe cases, recovery can take years. Symptoms also may remain dormant, until they are triggered by an event later in life. "We're still readjusting, we never stop readjusting," said Vietnam War veteran Jay Johnson of Harlem, moved by the Juilliard performance.

Doerries doesn't pretend to be a therapist, but he counts history as an ally to his healing intent. He cites the influence of the aforementioned Shay, author of Achilles in Vietnam, who theorized that a primary purpose of ancient Greek theater was to reintegrate warriors into a democratic society. "These stories were written by veterans, for veterans," said Doerries, noting that Sophocles was twice elected general. "They helped heal soldiers, and so did the communal act of bringing soldiers together in the theater. My thought was, 'Why couldn't they serve the same function today?'"

The Greeks' engagement in armed conflicts for most of the fifth century BCE supports the reintegration idea, McCulloh said. "A number of plays deal with the Trojan War. Warfare was a constant experience during the time of the Greek tragedians, and Sophocles and Euripides were reaching the peak of their creative powers during the Peloponnesian War between 431 BCE and 404 BCE." Schulman added that several Native American tribes developed readjustment rituals for their returning braves.

Destiny seemed to cast Doerries in the role of a PTSD activist; his upbringing and Kenyon years blended early exposure to psychology, the military, and the theater that laid the foundation for The Philoctetes Project.

The son of psychology professors, Doerries grew up in Newport News, Virginia, a Navy town, and studied classics at Kenyon, where his interest in the translation and performance of Greek drama culminated with his senior thesis—the production of an outdoor student performance of The Bacchae, by Euripides, in a makeshift amphitheater on a hillside near Horn Gallery. "It was spectacular," recalled McCulloh. "I was in the audience every night, and Bryan's The Bacchae was one of the few productions of a Greek tragedy I have seen to really have come off right."

Doerries recruited dance students for his Greek chorus, spotlighted a spying king in a tree, and introduced the young god Dionysus in an old Buick, rocking on its shocks with blasts from its stereo. He warmed the chilly March evenings with a bonfire and coffee for the crowd. "It's a lamentable shame that most classical theater companies do Shakespeare and little else," Doerries said, "but these plays should not be relegated to the ivory tower as museum pieces. They are living, breathing organisms, and I got to the point at Kenyon where I couldn't translate them unless I was working with actors, designers, dancers, and musicians."

His instinct for their appeal proved to be correct when a group of students, returning from a fraternity party, serenaded him with choral verses from the The Bacchae outside his apartment window at 2:00 a.m. Years later, under more sober circumstances, soldiers reprised the students' homage. "They came to me and quoted lines verbatim from the text, after hearing them just one time," Doerries said. "For me it was a dream. No theater-going audience ever remembers your lines on the spot."

A Rhodes scholar candidate at Kenyon, Doerries pursued his passion for "performance translations" after earning a master's degree at the University of California at Irvine and settling in New York as associate executive director of the Alliance of Young Artists and Writers, a national nonprofit organization that presents the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards.

Although he continued to produce performances of his translations, he failed to make the connection between Sophocles and PTSD until news reports surfaced a few years ago about the high rates of suicide and homicide among veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan, and the inadequate treatment the wounded were receiving at Walter Reed.

The revelations reminded him of Ajax, who slipped into a suicidal depression after the Trojan War, and Philoctetes, a cripple left by his men to fend for himself.

"It suddenly dawned on me that Ajax was a textbook description of PTSD and Philoctetes was more relevant now, in light of the Walter Reed scandal, than it was in 409 BCE. When I realized that, I went back and rewrote every word of my translations. I became convinced that military audiences would understand these plays on a fundamentally different level than civilians, and my ambition was to present them to a military audience, which sharpened my approach."

His ambition began to become a reality in January 2007, when Marine psychologist Captain William P. Nash made a surprising reference to Ajax in a New York Times article about adjustment issues confronting returning soldiers. "Naturally, I contacted Nash and he immediately responded by inviting me to present Philoctetes at a USMC combat stress-control conference," Doerries said. "The Marines seem to be the most aggressive branch of the military regarding PTSD. They were the first to open their doors to me."

More than two hundred and fifty Marines and their families attended the performance, held in San Diego in August. They reacted with applause, and a few tears. The success of that reading led to the Juilliard performance, and to another on November 19 for three hundred military leaders at a Department of Defense conference in Fairfax, Virginia.

Good Night and Good Luck), Emmy Award winning actor Paul Giamatti (Sideways), and Broadway stalwarts such as Bill Camp and Elizabeth Marvel. "Reading those scenes for the Marines in San Diego was one of the greatest highlights of my career," Camp said. "It is a privilege for me to speak those words and lend whatever skills I have to raise awareness about a subject that needs to be addressed."

Good Night and Good Luck), Emmy Award winning actor Paul Giamatti (Sideways), and Broadway stalwarts such as Bill Camp and Elizabeth Marvel. "Reading those scenes for the Marines in San Diego was one of the greatest highlights of my career," Camp said. "It is a privilege for me to speak those words and lend whatever skills I have to raise awareness about a subject that needs to be addressed."

T>he novelty of The Philoctetes Project has generated national and international news media coverage, but Doerries cares most about the attention it receives from active-duty military and combat veterans such as Jose Vasquez, of New York City, who served fifteen years in the Army.

"I think the narrations are timeless," Vasquez said after watching the Juilliard presentation. "The weapons may have changed, but the results are the same as they were centuries ago. We're still human beings killing each other."

Gambier, Ohio 43022

(740) 427-5158

Delicious

Delicious Facebook

Facebook StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Digg

Digg reddit

reddit