Volume 31 Number 3 Winter 2009

In this Issue

Features

- Kenyon's Own

- Out of the Ashes

- Peirce Hall Reborn

- Ancient Empathy for Warriors

The Editor's Page

- Restoration Drama

Along Middle Path

- Going Solo

- Seen and Herd

- Jersey Boys (and girls)

- Sound Bites

- Kenyon in the News

- The Hot Sheet

- Gambier is Talking About...

Sports

- Sports Round-Up

- Gaining Something In Translation

Books

- The Heart of the Matter

- Reviews

Office Hours

- Musings: Beginner's Mind Over Matter

- Not in my Job Description: Lyrical Baker

- Burning Question for Jennifer Delahunty, Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid

Alumni News

- PTSD Sleuth

- Driveway Moments

- Obituaries

- Alumni Digest

The Last Page

- Peircing Memories

By Mike Harden

Related Stories

The Victims

Nine Kenyon College students died as a result of the 1949 fire.Voices

The voices of the Old Kenyon fire, though diminished by time, are yet many. They are impassioned, particular, and clear.Web Extra: The HOurs After Midnight

Martha Gregory '10 has produced a documentary about the Old Kenyon fire. Watch the video, or read about the project.

Ghosts

You've heard plenty of Kenyon ghost stories over the years. But here's one you probably haven't heard.

A Nurse's Tale

Jackie Snyder McClain, a Kenyon date on that fateful night, cared for the injured and the dying. Read her story.

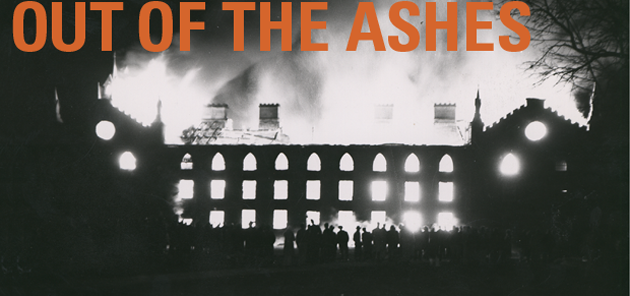

Jackie Snyder McClain, a Kenyon date on that fateful night, cared for the injured and the dying. Read her story.Sixty years after the fever-dream horror that claimed the lives of nine Kenyon students and rendered a ruin of Old Kenyon, the school's chief architectural emblem, William Wenner believes that he played a unique role among all who survived the February 1949 tragedy.

"I was the first one who saw it, as far as I know," Wenner '52 recalled of the fire from his home in Maryland, where he is a judge in that state's Court of Special Appeals. "My room was in Middle Kenyon. I was on my way to it and I passed by the parlor. When I glanced in, there was a window to the far right. I could see the fire running up the drapes. I knew there was a fire extinguisher at the bottom of the steps. I ran down, got it, and started back up to the first floor. I was literally blasted away from the doorway to the parlor by a wall of smoke. It cost me my eyebrows and a good bit of my hair." He stumbled out the basement exit to alert the fire department. Kenyon's worst nightmare had begun to unfold.

Although six decades have elapsed since the College's most grievous tragedy occurred, the accounts of those who survived the fire remain both vivid and anguished. These Kenyon graduates, today in their eighties, recall a winter night that began in frolic and revelry, with a Saturday dance christened the Sophomore Shipwreck, though it ended in chaos and death. On the eve of the sixtieth anniversary of the fire, the collective memories of eyewitnesses to the tragedy paint a comprehensive picture of a catastrophe that began when a few errant sparks from a hearth in the first-floor parlor of Middle Kenyon escaped a flue, then kindled in a tinderbox space between floors before exploding in a wall of flames. In the aftermath, fire investigators were unanimous in their contention that, while sparks escaping a flue caused the fire, no visual inspection beforehand could have detected the risk.

Robert Joseph Levy '52, now a professor emeritus of law at the University of Minnesota, remembered searing details: "In the Middle Kenyon parlor at about 3:30 a.m., I was just in time to help carry Marc Peck, unconscious, to his room across from mine to help get him undressed and on the bed. I noticed that it was ten to four only because I stopped to set the alarm. The smell of smoke awakened me.

"I walked to the window seat. I remember leaning out. Flames lit the hallway window on the second floor below. There was Ernie Ahwajee, standing in the stairwell to the basement directly below."

Levy rousted roommate Robert Millar and headed across the hall to awaken Marc Peck. Thick smoke laced by ribbons of flame drove him back. He and Millar made ready to leap, Levy volunteering to jump first. He flung himself at the bramble of winter-brown ivy clinging to the side of the building, hoping to slow his fall. The knot of bramble at which he lunged gave way and he plummeted more than three stories into an outside stairwell that ran from the parking lot behind Old Kenyon down to the basement of the building. Something ripped at his nose on the way down, and he sprained both ankles when he landed. But he was alive.

Inside Middle Kenyon, not far from where Levy landed, senior Warren Sladky could only feel and hear the tumult of escaping students and the growing intensity of the fire. Sightless from birth, he would later explain to a Cleveland Plain Dealer reporter that when the fire broke out, "I got up and opened the door into the hall. I was enveloped in smoke and heat, so I closed the door and dressed quickly, putting on my topcoat. Boys were racing through the hall, crying hysterically ... I could hear them climbing down the vines and the fire escape."

Sladky knew he would have to leave behind the two chief implements that aided his communication with a world he couldn't see—his ham radio equipment and his Braille typewriter.

"I left the room," he said, "and trying not to become confused walked the length of (the hallway) and out the front door."

Outside Old Kenyon, students watched helpless as the fire worked its way up the middle of the old building, then fanned across both east and west roofs and began burning downward.

It was a heartbreaking end to a night that had begun with no purpose more weighty than providing Kenyon's men with a break from their studies, perhaps a date for the night, and a generous helping of high camaraderie and low beer. The Rhythm Masters, an Akron band, entertained a throng that had been instructed to dress as they would prefer to be clothed were they to be stranded on a South Seas island. The set for the show was elaborate. Student Paul Newman '49 produced a campy, all-male revue featuring overweight men in tutus. For those who were light on their feet and heavy on acrobatics, two jitterbug contests were held.

Many of the dates of Kenyon men that night had arrived from the campus of nearby Denison University. Bill Porter '49, Student Council president at the time, recalled that Denison males were still smarting after one of Porter's classmates—a pilot and veteran of World War II—had scattered leaflets from the skies above Big Red's campus, appealing to its young women to visit Gambier's all-male college and take in the social life. Many had.

On the night of Sophomore Shipwreck, after the Rhythm Masters concluded the evening with some variation of "Goodnight Ladies," most of the dates of Kenyon students were deposited at the homes of faculty and staff who had agreed to accommodate them overnight. As for the men (and some of the women), the end of the dance signaled the beginning of Round Two of beer parties around the quadrangle.

Most of the revelers had turned in for the night by the time the fire began. As word of the calamity raced through the other residence halls, students rushed from their quarters, chinos pulled over PJs, and gaped in stunned disbelief as the 1827 landmark, said to be the oldest Collegiate Gothic structure in the nation, was reduced to rubble.

As fire crews from Gambier, Mount Vernon, Danville, and Newark were rushing to the campus, students manned the hoses, playing water over a fire that had gained too much of a foothold to be suppressed. The fire escapes on the rear of the building might have saved more lives had they been conventional step-and-platform assemblies such as those often seen on apartment buildings. Instead, they were simply a vertical succession of steel rungs seated in the brick and mortar between windows. To reach a rung, students were compelled to leap sideways from the window ledges of their rooms. It is not clear whether the two students who died of injuries suffered when they leaped from the third floor were trying to catch hold of rungs or were jumping in panic to escape the intense heat.

The night of the blaze was not without its heroes. Sophomore Edwin T. Collins, a bodybuilder from Pittsburgh, was sufficiently agile to jump from a window to the rungs, where he planted himself, coaxing those still trapped to jump to him. The late Will Pilcher '51, Collins's roommate, heeded the plea, remembering several years ago at the time of Collins's death that he and Leon A. Peris '51 both owed their lives to the bodybuilder: "The night of the fire, I was shaken awake by Ed, who had been in a scuffle with a Delta Phi, and was having trouble falling asleep. After I was up, we tested the door and found that the hallway was already full of flames. Ed then proceeded to the window and ... was able to jump across and reach the fire escape ... Ed guided me calmly out on the ledge, then had me push off with all my might towards him. Holding on to the fire escape with one hand, he caught me with the free hand and my momentum carried me to the ladder ... On his way down, Ed heard Lee Peris crying out for help from the room below and repeated this rescue procedure, but this time with severe facial burns from the heat."

For his valor, Collins would later be awarded the Carnegie Hero Fund Commission's Bronze Medal.

The heroism of others, though not as spectacular as Collins', was remembered long after the blaze. Kenyon's Dean of the College Frank Bailey, evacuating students and helping them remove their possessions, aggravated a back injury and was later admitted to Mount Vernon's Mercy Hospital; the problem, according to some accounts, plagued him for the rest of his life. Bailey was aided in his efforts to get students out of Old Kenyon by college president Gordon Chalmers.

As dawn broke and the fire slowly finished its business with Old Kenyon, college officials took a roll of Middle Kenyon, determining that six students were missing and presumed to have perished. A student assembly later in the day affirmed the same conclusion.

William Wenner recalled that when parents of the missing students arrived at Kenyon, they posed the possibility that their sons might have escaped the fire and made it to the woods adjacent to the building. Wenner and other volunteers formed search lines of eight to ten men, linked arm in arm, to comb the woods for survivors. They found none.

College officials, huddling with student leaders, decided not to cancel classes, though there was no obligation to attend, and many of the sessions were dismissed within minutes of convening.

Even as President Chalmers was pledging, in the fire's aftermath, that Old Kenyon would rise again, state officials were citing numerous fire violations of the old structure, including inadequate fire escapes, the absence of fireproof interior stairwells, and no fire-alarm system.

Charles Rice, an emeritus psychology professor and thirty-year volunteer with the College Township Fire Department, has written a book about volunteer fire departments in the Mount Vernon area. Two chapters are devoted to the Old Kenyon fire. Rice discusses his disagreement with Mount Vernon's fire chief in 1949, Carrol L. White, who argued that with an adequate water supply and sufficient fire equipment the building could have been saved.

"Even if they'd had ten engines," Rice said recently, "there would not have been enough water to fight the fire."

Afterwards, the walls of Old Kenyon were brought down, each sandstone block numbered carefully for the reconstruction, which was completed in the late summer of the following year.

As for the six students trapped in the fire, their remains were removed from the ruins and returned to their families. The lone exception to the recovery and return was student Stephen Shepard. His parents refuted the contention that the remains retrieved from the rubble were those of their son and, accordingly, declined to accept them.

Among all of the reminders of the Old Kenyon fire, the saddest is a grave in the cemetery adjacent to the quadrangle. Within it repose the charred bone shards sifted from the ruins and determined to be the remains of Stephen Shepard.

From an old photo in the Kenyon archives, Stephen Shepard, a dark-haired and handsome—if slightly brooding—young man stares back at the camera. Not far away in the archives is a picture of the old sandstone edifice in which he perished. Beneath that image, someone has scribbled the lines:

How oft 'neath thy walls in the hours after midnight

The stars growing dim and the waning moon low,

We sang the return of the gray morning twilight

And Kenyon's halls echoed the chorus below.

Gambier, Ohio 43022

(740) 427-5158

Delicious

Delicious Facebook

Facebook StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Digg

Digg reddit

reddit