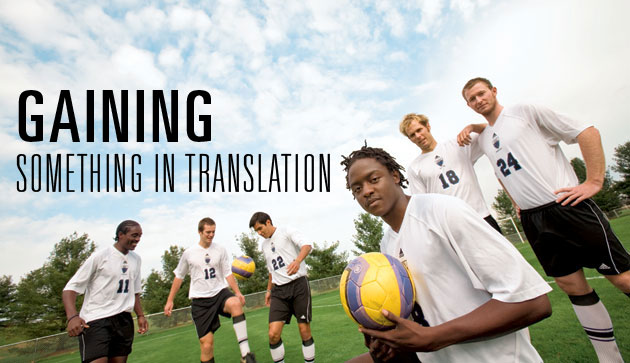

Keith Dangarembwa, a Zimbabwean, heads the ball out of the Lords' defensive zone. The ricochet finds the feet of Felix Hoffmann, a German, who evades a defender, glides forward, and passes off to Miguel Barrera, a Mexican, who darts up the sideline in an effort to generate a scoring chance for the Kenyon soccer team.

"Kenyon is committed to a diversified campus, and international students are a part of that," said fourth-year head coach Chris Brown, who adds British zest to the melting pot. "If you want to pull kids in from all over the world, then one sport you would anticipate could do that would be soccer, because it's the most popular game in the world."

The Kenyon roster also includes Tawanda Kaseke, another Zimbabwean, as well as a pair of New Zealanders in Dan Toulson and Reiner Bauerfeind. Each sports the Kenyon athletics shield on his chest, a Kenyon number on his back, and a style of play that is unique to his culture. Teammates describe Hoffmann as a direct and intelligent player. They rave about Barrera's creativity while remarking on the swiftness of Kaseke and the fearlessness of Bauerfeind.

These international student-athletes were immersed in the sport at an early age, when their distinctive approaches to the game began to develop. Some learned on dusty streets, some on well-groomed fields, and others in their own backyards. The individual setting helped shape each one's study of the game. So did the set-up. Playing with a makeshift paper ball forced composure in one, while a five-on-five game taught quickness to another. A spacious field inculcated the importance of possession, and a strong opponent required ingenuity.

"I think the sign of a good coach is to take all the abilities and experiences and mold the players into a smooth unit," Brown added. "That being said, you have to take into consideration the characteristics of your opponent, too. You can't prepare in a vacuum. You have to embrace what you're exposed to. Players adapt differently to teammates and opponents. They see the game and play the game differently. I'm not saying it's better or worse, just different. U.S. soccer, including play at the Division III level, is already in good shape."

And so the education continues. The international players hit American turf and contrasting styles grind. "It's a much more physical game here," Hoffmann said. "I've never spent so much time in the weight room."

"Yes, it's definitely more physical," Kaseke added. "I'm used to a more technical game. Here they'll just knock you off the ball. They'll play a lot of long balls, too, and for me it's like, 'Hey, what happened to the midfield?'"

Meanwhile, Bauerfeind tends to his own refinements. "I've always been taught to keep the ball moving. Even if it wasn't terribly productive, at least you'd keep the defense from closing in on you. Since I'm so used to moving the ball around, it always seemed natural to pass to a guy who was asking for it. Now, I don't always get it when I ask for it. It's frustrating, but understandable."

Despite, or maybe because of, the differences, the Lords have had great success. New ideas and better understandings spout from individual expression. Collaboration and creativity fuse with speed and power. The result: Kenyon owns a combined record of 25-9-4 over the past two seasons and has made back-to-back playoff appearances.

"This is a game that allows for freedom of expression, and now I'm playing it at a college that allows you to express yourself," Kaseke said. "Somehow it just all comes together."

—Marty Fuller

Delicious

Delicious Facebook

Facebook StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Digg

Digg reddit

reddit