Day by day, Bruce Olmstead built a house, "a cottage sort of thing." He conceived the plan, contemplated the cost, found the lumber and hardware, and went to work.

The walls tumbled down when he heard the excruciating metal scrape of the peephole sliding open in the three-inch-thick wooden door of his solitary cell in the Lubyanka Prison in Moscow. Interrogation would begin again.

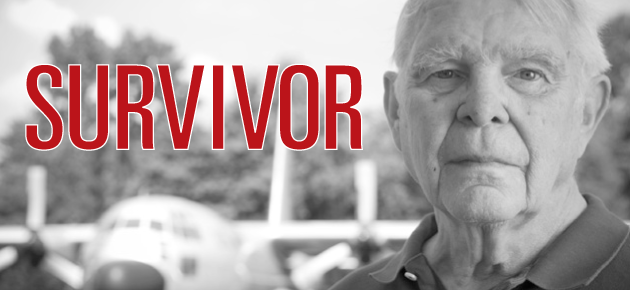

Fifty years ago, the Cold War loomed over history. Olmstead was fated to play a role in one of that conflict's notable chapters-as an aviator, and as a prisoner of the Soviet Union.

July 1, 1960. Olmstead, a U.S. Air Force first lieutenant who had "majored in ROTC" at Kenyon in the class of 1957, took the copilot's chair in his RB-47H. As the six-engine Stratojet rumbled down the runway at Brize-Norton Royal Air Force Base in central England, the six-man crew chewed on a heads-up from the detachment commander: "Be careful, because they're going to try to shoot you down today."

The crew was part of the 55th Strategic Reconnaissance Wing. The men had trained together for about a year at Forbes Air Force Base in Topeka, Kansas. "We were colleagues," Olmstead said. "We were close." They had arrived in England on June 14, 1960. Three days later, Olmstead turned twenty-five.

The plane, built for bombing, was the muscle of the U.S. Strategic Air Command fleet in the 1950s. This one, nicknamed Snoopy, was converted for reconnaissance. Its erstwhile bomb bay was filled with surveillance gear operated there by a three-man electronic-signals-intelligence team, called crows or ravens.

"It was not a very forgiving airplane," Olmstead said. Designed to take off at about 183,000 pounds, this one flew at 225,000.

The flight was the crew's first "operational mission," and the first U.S. surveillance flight targeting the Soviet Union since the May 1, 1960, downing of the U-2 spy plane piloted over the U.S.S.R. by Gary Powers, a former Air Force pilot then in the employ of the Central Intelligence Agency. The incident embarrassed President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who had first described Powers's over-flight as a weather mission. In the aftermath, Eisenhower had suspended air activity over Soviet territory.

But now the game was on again. Olmstead and his crew were assigned not to enter Soviet airspace, but to get the Soviets' attention. The idea was to measure the enemy's defense and communications systems. The flights were often called "ferret missions." It was "kind of hide-and-seek," Olmstead recalled.

He became a captain the moment the plane's wheels left the earth. The promotion was put in place for those on "particularly touchy missions" as a means of at least temporarily boosting compensation.

"We were into the Cold War big time," said Olmstead. "It was a very dangerous time in the world. Given the circumstances, that they just caught somebody 1,600 miles inside their country, they were understandably touchy."

For a mission expected to take as long as fourteen hours, the plane was flush with fuel, but not enough for the whole flight. Mid-flight refueling was required—in this case, off the northern coast of Norway. "That's hairy stuff," Olmstead recalled. "You're seventeen feet from another airplane going 460 miles an hour. Fortunately, you're high enough (at 30,000 feet) so it's not bumpy."

Rounding the Norwegian coast, the crew swept along the coast of the Russian Kola Peninsula, turning northeast after passing Murmansk. The Soviets would later contend that the American plane encroached on Soviet airspace, penetrating the twelve-mile ring it claimed for its territorial waters. The United States insisted the plane ventured no closer to the Soviet Union than thirty miles.

For defense, the crew relied on a pair of 22-millimeter cannon in its tail. "Do you feel vulnerable? Yeah," Olmstead said. "All of a sudden I saw this dude sitting right outside my canopy behind the right wing. I had no idea where he came from."

During the Cold War era, airborne encounters took place now and then. Olmstead had heard of rival pilots waving at each other from their cockpits. There were stories of American pilots sharing a Playboy centerfold with their adversaries or, depending on the mood, "flipping them the bird."

But this confrontation took a deadly turn.

The MiG-19 fighter that appeared next to the American plane was piloted by Lieutenant Vasili Poliakov, who said later, "I was on combat duty to intercept, and I flew up to find the enemy. I signaled the plane to follow me. He wouldn't obey. I radioed my base, and asked what I should do. An order came back, 'Destroy it.' I opened fire and the plane started to burn."

Olmstead remembers no such signal. The Russian pilot dropped back "and fired a couple of shots. I emptied our guns on him, but he had disabled my radar, my fire-control system. He jammed it. All I had was a little handle so I could move them [the guns] around. I emptied about a thousand rounds on him. If he hadn't jammed the radar, I could have locked on. And then he pumped at least two 33-millimeter cannon shells into the two and three engines. We immediately went into a spin."

With the jet out of control, the commanding officer and pilot, Major Willard Palm, hit a dashboard switch, ringing a bail-out bell. "When you bail out, things start happening in a big hurry," said Olmstead. An explosive device shot the ejection seats from the plane. "You had a tremendous acceleration, and most people who bailed out in that kind of a seat were black-and-blue from behind their knees to just behind their shoulders."

Olmstead suffered a broken back. "I got a compression fracture of the twelfth thoracic vertebra when I bailed out. I was more or less paralyzed from the waist down. I knew it.

"They had an automatic parachute. You're in a free fall for 16,000 feet. It opened at 14,000 feet. Then you're hanging in a parachute above the Barents Sea, where you know the water temperature is about 31 degrees."

All hands escaped the plane but one parachute did not open, and Olmstead saw the airman plunge into the sea. Four of the crew died, including the "crows" and Major Palm. Of the bodies, only Palm's was recovered. Olmstead and the navigator, John McKone, were left to bob in six- to seven-foot swells, about a mile apart. They could not see each other, but they could see flames from the Snoopy as it was swallowed by the sea "quite a ways away from us."

A survival kit included an inflatable life raft along with tools, fishing line, a pair of socks, and a double-barrel .22-caliber Hornet rifle, intended for use in small-game hunting. Olmstead scrambled into the life raft and dumped open his kit. A pointed file, missing its cork stopper, promptly poked a small hole in the boat. "There were no patches at hand, so I sat in the cold water. I was in shock. I was terrified. I knew I was going to die," he said. "I was thinking how cold it is. I loaded my rifle and put it in my mouth. I got it all ready to go, and then I thought, 'If they find me, Gail will be really pissed.' So I threw it overboard."

Back in the U.S.A.

Gail was in Kansas with the couple's daughter, Karen, who was born when her father was flying over the North Pole on a training mission in 1959. The couple had married in December 1957.

They met during a Kenyon dance weekend, at a Beta Theta Pi party. She was a student at Ohio Wesleyan University. "I was just sitting on a table having a drink, like you're supposed to do, and she was with another guy. He went to get her a drink, and she pulled out a cigarette. I lit it for her and we struck up a conversation." He remembered the name and the face.

After that, Bruce invited Gail to visit often, and a treat for her was the rich supply of milk by the pitcher in Peirce Hall, where Bruce was a head waiter. He also played lacrosse. "We were Kenyon men in those days, and we very seldom let anybody forget that," he noted wryly.

They now live in Annapolis, Maryland, in a handsome ranch home with a slanting view of the Chesapeake Bay. Olmstead is a retired Air Force colonel, and the slight hitch in his step is thanks, in part, to the broken back, which also cost him an inch of his six-foot frame.

His blue-eyed gaze is steady and penetrating. He makes conversation easily but wastes no words. Described as "dashing" three times in two pages of the 1962 book The Little Toy Dog, which recounted the events of 1960, he still fits the part. He likes his wit the way he likes his martinis: dry. He long ago gave up smoking, and he betrays no outward evidence of the lung cancer he battles.

Olmstead is a New York native and the son of an accountant who sent three sons to Kenyon. His mother hoped Bruce would become an Episcopal priest. "I just always wanted to fly," he said. "The whole idea of having thousands of parts and wires and tubes and motors and other stuff all in the same place in the sky and working in harmony was the attraction," he said. "It is hard to explain, but flying at night in the polar region when the Aurora is active is almost a spiritual experience. You can actually fly among the vertical shafts of light. It is at once eerie and awesome."

He became an ROTC cadet group commander during his senior year and, after graduation, headed to flight school. "The day I went into the Air Force, my mother and grandfather took me. My mother started weeping. She said, 'Brucie, they can't make you fly an airplane if you don't want to.' But I wanted to.

"My granddad gave me a big hug, and he said, 'Brucie, don't never go nowhere where you doesn't want to get caught dead.' Everything you do has a consequence."

Olmstead chose reconnaissance work. "It was one of those decisions that you make based on faulty information," he quipped. "I figured the reconnaissance people wouldn't go anywhere until after the war was over... and I also thought I wouldn't have to go overseas very often like the bomber guys did."

Looking back, Gail said, "I didn't know about the danger. I didn't know they had stopped all flights after Gary Powers was shot down, and I didn't know that Bruce was on the first flight after that. They didn't tell us very much."

With her husband in captivity, she was "treated beautifully" by the government, he said. "I think I got through it by trying to look optimistically at everything," Gail said. "I built myself up. He's going to come home and, hopefully, sooner rather than later."

Solitary Confinement

Olmstead was able to keep his chest above the freezing water that seeped into his life raft, saving his life. A Russian fishing boat found the airmen after about six hours. The fishermen kept the men apart but comforted them with tea and honey.

The Soviets, cynically, joined the American search-and-rescue effort before announcing after ten days that they had downed the jet. The airmen found themselves in Lubyanka Prison, also the headquarters of the KGB, the Soviet intelligence agency. Olmstead's windowless cell measured about nine by six feet. The naked light bulb never blinked. He could hear beatings in the hallway and, sometimes, gunshots he took to be executions.

Ten days after he reached Moscow, his broken back was diagnosed. "I had trouble walking. The cell had a steel cot in it. They put the head up on some two-by-fours and tied my shoulders to the top of the cot, and they put a rope around my feet with a sand bag to put me in traction. For Lubyanka Prison, it was pretty good."

Interrogation took place in the cell during the seven weeks in which Olmstead was in traction. Questioning was "incessant," running up to six hours at a time. The Soviets "knew quite a bit about us" and were aware the crew had spent time at Strategic Air Command headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska, for a mission briefing. The Soviets considered them spies and were intent on wringing confessions that would implicate the American president in ordering the mission into Soviet airspace. They hoped to put Olmstead and McKone on trial with Powers.

Those confessions never came.

"They worked very, very hard to get an admission of guilt and also to hang Eisenhower," Olmstead said. Their lives were threatened, but they were not beaten. "You ignore them as much as you can. I got belligerent a few times, and I said, 'Where do you get off asking me all these questions?'"

Sleep deprivation was a favorite tool of his captors. "They tried to disorient me. We didn't know whether it was morning, noon, or night." Rice, sometimes with bits of chicken, was served at odd hours.

"You absolutely lost any privacy," he said. "There's a blessing in being in solitary, in that time really ceases to exist in terms of hours and minutes. At least for me, time was measured by one event that came after another event. There was an interrogation and then there was a meal. I couldn't tell you very much what happened between those events."

Mental exercise sustained him. He built that house, and he counted the hairs on his arm. He used matchsticks and material from cigarette packs to fashion a cross, hidden under his bed and useful for his daily prayers.

"It was colder than hell in there," Olmstead said. "They would bring a pot of what they called tea in the morning. It was just warm water. By the afternoon, it froze."

The man who weighed 200 pounds the night before his mission dwindled to 117. "I wasn't looking very good. It bothered John." The airmen met once during questioning, and, in a 1996 interview, McKone recalled, "I didn't recognize him. And I said, 'Bruce? Are you Bruce Olmstead?' Because I noticed something familiar about his face and eyes. And he burst out in tears."

The men were reunited once more, briefly, on Christmas Day. A miniature deck of cards Olmstead had created from foil-and-paper cigarette wrapping became a gift for McKone.

Powers had been convicted of espionage on August 17. Olmstead and McKone, steadfast in their denial of guilt, never faced trial. That November, Olmstead was brought before Roman Rudenko, the prosecutor general who helped convict Nazi leaders at Nuremberg after World War II. With Rudenko was KGB head Alexander Shelepin. "It was very cleverly staged, very intimidating," Olmstead recalled. "It was late in the afternoon and I was seated across the table from this very imposing figure. I was looking into the sun, which was setting, and it was red."

Rudenko asked Olmstead if he was guilty of espionage. "I said no, and that really annoyed him. I looked him right in the eye, I figured it couldn't hurt, and I said, 'You owe me an explanation. You sent your pilot out and he killed four of my crew members. Why did you do that?'

"I was taken right out of the room." Disappointed interrogators then told Olmstead, "We're going to have to start the whole thing over." The prisoner shrugged it off. "Being snotty to this guy wasn't going to make much difference."

Some letters from home reached Olmstead in prison, including a coded message from Gail about her second pregnancy. When she wrote that "Conrad Brent" was coming for a visit, Olmstead understood that the use of his old community-theater stage name meant that another child was on the way. That prepared him for later taunts by his interrogators who tried to bully him with news of the pregnancy gleaned from Western news reports.

In a Christmas letter to Gail, Bruce said, "As I write this you are probably all reading Christmas poems, opening packages covered with pretty paper." He finished: "I hesitate to end this letter, honey, because it must end in the same old way. But, honey, we can hack it if we stick together the way we have."

At the Highest Levels

The July 1 incident captured the attention of the world. The United Nations Security Council heard the debate later that month. In discussions with U.S. diplomats, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev insisted his country had the right to defend itself but wondered how the incident might affect the 1960 presidential election in the United States and set back efforts at improved relations.

The November election, which would send John F. Kennedy to the White House, opened a window for negotiation. The two sides crafted an agreement for a prisoner release, which called for a joint announcement in Moscow and Washington, a pledge by the U.S. to discontinue U-2 flights over the Soviet Union, and a U.S. promise not to exploit the incident for diplomatic or political gain.

Kennedy was inaugurated on January 20, 1961. On January 25, the captive airmen were each given a shave, a suit of clothes, a coat, and a beaver hat. Olmstead carried a final pack of Russian cigarettes. His clothes and the cigarettes are on display in the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio.

Taken before Shelepin and other "smug functionaries" a final time, the airmen were told they were "absolved of personal responsibility" and would be released. Asked if he had parting words for the Soviet people, Olmstead barked, "Let's not miss that airplane."

Taken before Shelepin and other "smug functionaries" a final time, the airmen were told they were "absolved of personal responsibility" and would be released. Asked if he had parting words for the Soviet people, Olmstead barked, "Let's not miss that airplane."

Kennedy announced the release at his first news conference. The men were flown to Andrews Air Force Base, outside Washington, where they were reunited with their families and met the new president. They were then ushered to the White House. "It was quite an experience," Olmstead said. "Two of us lived through it. And President Kennedy was clever enough to get us out."

The president chatted easily with the men while coffee was served in the Red Room. "He said he was glad to have us back. He took us aside and told us he was having some real difficulties in Southeast Asia and that we could help him greatly if we really wouldn't bad-mouth the Russians much because, apparently, they made an agreement with Khrushchev that this wouldn't be used as propaganda.

"So when the president takes you aside and asks you to help him out, you said, 'Yes, sir.'"

The Kennedys were "very charming," Olmstead said. Gail remembers a "wonderful" visit that included tea with Jacqueline Kennedy. "They were very lovely and genuine, very gracious," she said of the Kennedys. "I remember that Jackie asked questions about our letters that I thought were classified. I was so worried about saying anything."

The reaction in the U.S. was "overwhelmingly enthusiastic," reported Time magazine on February 3 in an issue with the men on its cover.

After a long debriefing, and after the military police assigned to protect his home moved on, Olmstead resumed his career. He became an Air Force test pilot. He earned a master's degree in political science at Auburn University. In 1971, he was assigned to Kent State University as commander of the Air Force ROTC detachment and professor of aerospace studies. His goal was to win back academic credit for Air Force ROTC classes, something that had been stripped away in the wake of the 1970 shootings of students by National Guard soldiers at Kent State during Vietnam War protests. After four years, he accomplished that mission.

Olmstead then joined the Defense Intelligence Agency. After two years, frustrated by Pentagon bureaucracy, he seized an opportunity to become the air attaché assigned to the U.S. embassy in Copenhagen, Denmark. He learned Danish, as did Gail, and they spent three years overseas. He visited the Soviet Union and, over the years, became friends with and hosted Russian military veterans at his home.

The couple endured the adult deaths of daughters Karel and Betsy. Their surviving daughter, Karen, is now the dean of the School of Science and Technology at Salisbury University in Maryland.

Bruce and Gail have five grandchildren. He retired from the Air Force in 1983, became a home-remodeling contractor, bought and sold a sailboat, and spent time building model sailing ships.

Olmstead acknowledges the effects of traumatic stress. A recurring nightmare has him released but then returned to prison. Only recently has he overcome the need to keep a light on in the bedroom, and he still listens to a radio throughout the night to help him sleep.

"I enjoyed flying very much, and I enjoyed the embassy work very much," he said. "Aside from seven months in Lubyanka, it was a very satisfying and a very happy career."

His Kenyon experience served him well, even if the only nightmare that rivals the prison dream is the one about the fear of failing comprehensive exams.

Delicious

Delicious Facebook

Facebook StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Digg

Digg reddit

reddit