The More Things Change...

by Jeffrey Bowman

The start of the academic year inevitably inspires a flurry of observations about "today's students." Experts come forward to describe what distinguishes our newest students from preceding generations. If the experts are to be believed, the news is not especially encouraging. Students spoiled by helicopter parents are self-indulgent, feckless, and can't fend for themselves. They demand ceaseless entertainment and ever-more-outrageous luxury amenities. Raised on American Idol, Call of Duty, Facebook, and the enervating thrum of constant texting, they are self-involved and easily distracted. We are warned emphatically that the students who slouch before us in 2010 are importantly different from any who have come before.

As a historian, I spend my days thinking about change and continuity. Like most historians, I'm temperamentally inclined to view claims like these about sudden, dramatic change with skepticism. An unsystematic glance at evidence from the period I know best (the European Middle Ages) suggests that today's students may not be so different after all. Where they are different, they are no worse.

In his Confessions, Augustine of Hippo complains bitterly about the violent student mobs who roamed fourth-century Carthage. The license of students was so "foul and uncontrolled" that he sought a teaching position in Rome, where he believed he would find more committed, civilized students. Roman students were less raucous, as Augustine had hoped, but he was dismayed to discover that they were also sneakier. Near the end of each term, they stopped attending lectures in order to avoid paying their teachers.

University regulations tell us a good deal about the types of student misbehavior that prompted concern in the Middle Ages. Oxford promulgated strict residency requirements to limit the time students spent in taverns and brothels. Cambridge's Peterhouse College prohibited students from possessing dogs or falcons, dicing, engaging in trade, and socializing with actors. Students in Heidelberg ran afoul of authorities for capturing doves, attending fencing schools, and dancing during Lent. A thirteenth-century guide to student behavior warned against fornication, dicing, and the excessive use of spurs while riding. The famous preacher Jacques of Vitry complained that students came to the university in Paris mainly because they were vain and greedy, faults exacerbated by the city's corrupting influence. Jacques was an admittedly crusty observer, but others made similar complaints about students carousing, using coarse language, insulting their teachers, strumming guitars instead of studying, and spending their summers aimlessly wandering from one place to another.

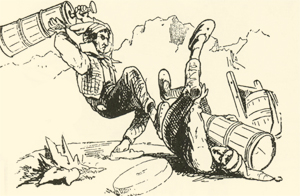

Medieval critics thus paint a bleak picture of feckless and undisciplined students. At times, student misbehavior went beyond these personal shortcomings and became a threat to social and political order. In 1220, students in Paris began a riot that resulted in several fatalities. During carnival of 1228-1229 in Paris, a quarrel between students and a tavern owner over the bar tab degenerated into a violent brawl. The following day, a mob of students broke into the same tavern, distributed all there was to drink, and went forth to amuse themselves with disastrous consequences. A riot in Oxford began when students complained to a tavern-keeper about the quality of the wine and, to drive their point home, threw wine-filled vessels at the tavern-keeper's head. The ensuing mayhem lasted days and left several dead. Even without brawls, students could be violent. Thirteen of the twenty-nine coroner's reports that survive from Oxford from the early fourteenth century record murders committed by scholars. University administrators apparently had good reason to prohibit students from bringing swords or knives to class.

How then do "today's students" stack up against their medieval forerunners?

Some things apparently change very little. It turns out that groups of intoxicated nineteen-year-olds tend to do a poor job of assessing risks regardless of the century.

In other areas, it is difficult to gauge change or continuity because of shortcomings in the surviving evidence. Medieval sources remain frustratingly mute on subjects of keen interest to modern educators: the wearing of baseball caps indoors, students' baffling reluctance to attend to the demands of nature before class begins, and the bringing of bowls of cereal to class, to name only a few.

In a few arenas, we might celebrate modest progress. Observers like Jacques of Vitry lamented that students devoted too much attention to their hair and were too fastidious in their dress. On this count, we might reassure Jacques that things have improved. He would be gladdened to know that the sartorial standard in the early twenty-first century is to attend class looking as if you had spent several days playing rugby in your pajamas in a part of the world without running water. There is progress, too, in the realm of weapons. Unlike their medieval forerunners, few Kenyon students seem inclined to bring swords to class. Given a choice, most faculty members prefer easily distracted students to well-armed ones. And, finally, there is good news in the millennium-long war on student dicing. Of the fifty-five students I'm teaching this semester, only eleven admitted to having handled dice in the past month. Victory is not yet complete, but we have the dicers on the run.

If we take the longer view, the picture looks promising.

Delicious

Delicious Facebook

Facebook StumbleUpon

StumbleUpon Digg

Digg reddit

reddit